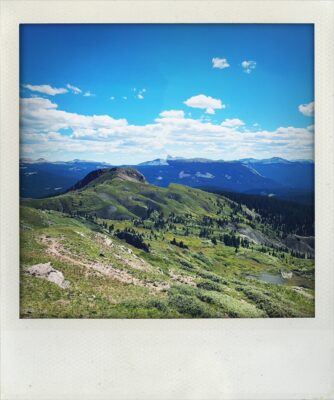

It is the kind of day photographers and hikers live for. I tramp among the lush undergrowth beneath a cobalt sky that will stay that way all day because the clouds I see are not ones to worry about. Recent rains have left behind a bounty of forage in their wake. From my first step on the trail, there has been something to look for—grouse, strawberries, raspberries and so many mushrooms. I have set out to climb a peak on my own, something I have never done even though I have summited more than 80 mountains. I am not a natural athlete and I have no sense of direction, so I get lost easily, but I am in pursuit of the rarefied terrain above treeline. It heals me and fills me with something I cannot name but deeply need right now. This peak has a clear trail to the peak, and I have hiked to the saddle just below the summit many times, so I feel like I have a good shot at not getting lost. I reach the top easily through the main route up the east shoulder, taking time on the way to notice the trail I want to take to get back down.

The summit is spectacular, and with the weather, I can stay there as long as I want. There are no puffy clouds with flat bottoms to watch signaling storms, no brutal winds to usher in an entirely different day that could push me down. Nothing but clear skies above and hard mountain rock below. I linger for almost an hour, which is a luxury. It is work to get to the top of even the easiest peak, but you don’t often get to savor that view, that bird’s eye look at the world. When I look for miles out onto the Earth from that high up, I effortlessly see the natural world that is easy to forget. It is a vast ocean of mountains and trees, dotted by our little islands of houses and towns stuck in here and there like archipelagos. It recalibrates my human-centered life and restores my place, my very small place, in this large landscape, and comforts me with the promise of my impermanence.

I am in this state of merging, of blissful peace, when I head down, lingering in my mind while my feet keep moving. I hit what I think is the point on the ridge where I drop down to the shoulder I came up, so I head that way. By the time I realize that I have taken the wrong route and descended too early, I am on a steep slope of unstable scree. I am deeply disappointed. I consider my options. It would be a soul-sucking swim to scramble back up, and the slope is too steep and rock too unstable to traverse. My safest option is to hike down to the flat basin below me and get back on the main trail from there. I see what looks like the same large clearing I passed through coming up on the, so I head that way. It isn’t a bad scramble, kind of fun, and once I am down in the trees, I start to see trails, which comforts me as I hope they will lead back to the main trail. I take a few, and one by one they either turn to head in a different direction or stop altogether.

Game trails.

Elk and deer don’t typically go straight to the parking lot, so these paths, which make for easy hiking through the thick forest, are actually not helpful. I finally reach the clearing, but when I get there, there is no main trail in sight. Even though I know they are game trails, I convince myself that following them will lead me back to the main trail, so that’s what I do for a while, still heading down and that, at least, feels good. The weather is wonderful, and buoyed by my false confidence and the ease of downhill hiking, I keep going until the trails lead me, of course, to the creek. So I think, fine. I will hike along the creek, because I know it will eventually hit the road. My five-hour round trip hike is now heading into hour seven, and I am not sure what the terrain is like between where I am and where I want to be. I have not seen a single person since hiking up. I have no cell service and I am getting tired. I have not rested because I want to know where I am first.

I have been hiking in the mountains for 25 years, and I know all the things to do when you are lost. I have done none of them. Finally, when I have been bushwacking for more than two hours, my body speaks loudly enough that my mind has to admit I don’t know where I am. I sit down on a fallen log, have a drink of water and eat the last of my trail mix. Shortly after I stopped moving, I am hit by a surge of emotions. I feel afraid and helpless, and a memory of feeling that same way 25 years before comes flooding back.

It was the kind of day that nobody would photograph. Gray clouds hung overhead and the landscape was a mottle of melting snow and dead grass that gave it the patchy diseased look elk have when losing their winter coats. Only the evergreens held color as muted earth tones dominated a landscape that was just waking up from a heavy winter. I had time to study that unloveliness around me because we were stuck. It was spring mud season, and the thick chocolate-colored clag had claimed our car. We normally wouldn’t drive out when it was this bad, but I was sick, on day three of a fever, and I had a deep, painful cough. I suspected that I had bronchitis or pneumonia, either of which would require antibiotics. To get those, we had to go to town. My boyfriend was driving not just because I was sick, but because he was the far better driver and the access road to our cabin–a sketchy drive in ideal circumstances– was nearly impassible during the height of mud season. Muddy roads are so tricky. Momentum is your friend, but too much and you could slide off or spin out. Too little and you end up where we were that day, and we were in deep.

Our cabin sat in a broad bottomland valley made by the confluence of two creeks. To get to the county road, we had to ascend our steep driveway and then follow a two-mile long easement dirt road, most of which was flat, except for a steep uphill S-curve section where we were now stuck. We had made it up our driveway because it was south facing and mostly dry, and across the flat stretch of road before the S-curve, gully really, that is north-facing and the primary drainage for the hill above it—an awful place for a road. It was, though, where the easement ran between our cabin and the county road. To get through it when it was thick with dark clay mud, you had to have the right amount of momentum—enough to safely make the curves, but not so much that you missed the curve and slid off down the embankment.

That day my boyfriend over accelerated and the Honda spun out, its back end surged ahead faster than the front and then sank into a deep pothole made by the freezing and thawing snow that settled there for the winter. He was instantly mad—maybe because we had been fighting, maybe because he was hungover, maybe just because we were stuck—and tried to drive out of it, and that sunk us to the axles. We argued because I wanted to leave early that day for town when the mud was hard and cold, but he wouldn’t get up. He had been drinking the night before, like many nights, which was probably the real reason we were fighting. By the time he had gotten out of bed to drive me in, it was almost 11 a.m. The mud had softened and it trapped us.

Trying to avoid the mud before I had to sit in the doctor’s office, I stayed in the car while he walked around and decided what to do. Sitting in the tiny interior of the 1983 Civic, it felt like the literal cage that had been closing in on my life. It had been a long winter for us as a couple, stuck in an isolated cabin whose unplowed roads were traveled on skis from November to mid-April. At the time, I would have said his drinking was the cancer that was killing us, but looking back from my 50s, I know it was more complicated than that.

The momentum we had when we met—an exhilarating chemistry followed by a plunging commitment—had faltered when we tried to merge our two very different selves that emerged when the honeymoon ended. I was a nerdy city girl who planned, wanted security and had no outdoor skills whatsoever. He was a natural outdoorsman and free spirit who thrived on walking through the world without plans, security or obligations. We were oil and vinegar, blended only when shaken by lust or passion, unwilling or unable to emulsify, leaving us separate and incompatible when stilled by the staid routines of life. Time was the real killer of our relationship as our differences created constant abrasion. We endured being stuck in that cabin together by creating temporal solitude: I rose before dawn and was asleep within hours of the winter’s early sunset. He stayed up past midnight and woke closer to noon. Most afternoons I was skiing or working, limiting our time together to some late afternoons and dinners.

It’s easy now to see that we wouldn’t last, but on that spring day, I had not given up. There was so much about our life I loved, so I chalked it up to cabin fever and being sick because I was still hopeful that we would find a way to blend. My seat in the Honda faced the forest just past our cabin, and I remembered the summer before when he had taken my hand just as the sun was setting and led me from our cabin across the field to that forest. The light was a butter gold that lingered as he laid out a blanket and built a small campfire. We sat together for hours, feeding twigs to the tiny blaze, talking and looking at the star-filled sky.

The car door opened.

“I’m gonna jack up the car and maybe I can drive out of it,” he said. When I didn’t move right away, waiting for his words to sink in, he added, “You have to get out of the car.”

I opened the door to only mud, black and deep. I wanted to stay as clean as I could since I still held hope we would make it to the medical center, but my first step sunk me to my ankles. I headed to a big rock about five feet away embedded in the hillside, each slow step slurped a sucking sound. I watched him stack floor mats on the mud to keep the jack from sinking, and as he cranked, the back wheels came out of the mud. The car was front wheel drive, so he put the remaining floor mats and some 2x4s under the front tires, hoping to get enough speed to reach a drier patch of road about 20 feet ahead. Twenty lousy feet, but it might as well have been a mile.

He got in the car, revved the engine, popped the clutch and surged forward, but not far enough. We got stuck again about four feet ahead of where we were. I watched from my rock as he repeated the process, the mats and boards muddier and more useless the second time, and the car moved ahead only a few feet. The dry patch was still yards away. He stepped out of the car, stared at the ground and walked around shaking his head.

“One of us has to push while the other one drives,” he said, not able to look me in the eye. He knew that I wasn’t fit for either task. I wasn’t very strong when I was well, and on that day I was so sick. I hadn’t eaten in a few days and I had the chills and weakness of a high fever. That left driving, and without someone who could work some magic with the accelerator, clutch and steering wheel, it didn’t matter how good the push was. I was no wizard behind the wheel. I felt tears build up at the back of my throat and I wanted to cry, but didn’t.

“I’ll push,” I said.

I slurp-stepped over to get behind the Honda, ankle-deep in the mud and drowning in emotion. At that moment, I hated him for his drinking, blamed him for our late start, but at the same time I loved him for how he took over, so capable in the wilderness, so dysfunctional everywhere else. And I hated myself for being the opposite—at ease in town, at my job, but at a loss out here, stuck in the mud on a curvy, hilly road.

“When I tell you, give it what you got,” he said as he revved the engine.

When I heard, “Now” I pushed with all I had, which wasn’t much. I couldn’t get any traction in the mud and nearly face planted, but was able to right myself with the bumper just as the car lurched. Boosted by the push, it slid not toward the dry spot, but diagonally on the liquid road and stopped again, sinking in, still six feet from the dry patch of road. I released the bumper and fell anyway, mercifully on my back. I was covered, the wheels were covered, and we were stuck again. Exhausted and muddy, I could barely hold the tears back as I realized that we were not getting out. I was not going to the doctor. We would have to wait for the mud to dry out or freeze—whichever came first.

“We can come back up in the morning, but we aren’t going anywhere now,” he said and started to walk back toward the cabin. I surrendered, sat back on the rock and let the sobs come. They weren’t just from that day, but ones I had held back for a winter’s worth of months feeling trapped in tension that, whether I knew it then or not, I had helped create by digging in to being right and shaming him with my saintly ways. I had constructed a well-built world in which he could never be right, his way could never work, even as I watched it work time and time again.

I cried out the anger and frustration and disappointment under that dreary gray sky, adding my tears to the tiny creeks that flowed all around me as the snow surrendered itself to the warm spring sun. Sitting there I felt afraid and helpless. Stuck. Not just in the mud, but in our relationship. I would like to say that I realized then that I had a part in it; that I saw how my pushing to always be right meant that he was always wrong. Looking back on it, I see how if I could have started showing him that I saw what was right in him and stopped shaming him for who he wasn’t, it may have led us forward to a better place. But I didn’t. Instead, I sat there, in that spot, wanting to disappear, to merge fully with the sodden ground, plant myself like garlic and rest until the Earth’s renewing power made me fresh, green, reborn.

I forced myself to get up and walk the mile or so back to the cabin, coughing hard and deep from the little exertion that required. When I got there, he was making a whiskey-and-coffee, a newly rolled cigarette on the counter.

“We’ll get out tomorrow morning and get you to the clinic,” he said. “You’ll be OK. I promise.”

He set his cup down and held out his arms. I fell into them, wanting with all I had to break out of the rut we were in and get back to the full feeling of free falling into love.

The next morning I slept in until just after dawn. I had taken ibuprofen, but my fever was still pretty high. When I got up he was already awake.

“I’m gonna get the car out. The ground’ll be hard now,” he said, and headed out.

My uphill walk to the car was the hardest part of the day as I coughed and wheezed each slow step up our driveway. By the time I got to the car, he already had it out of the mud and was waiting for me.

“Drove right out once I jacked it up,” he said, smiling.

“Thanks,” I said. “You are saving me right now.”

When we got back that afternoon, antibiotics in hand after the doctor had confirmed my bronchitis, we didn’t drive all the way in and instead left the car just off the road on a flat section between the county road and the uphill S-curves. The land wasn’t ours, but was vacant and we felt safe for the few weeks left of mud season. Walking down the road he slowed his pace to match mine and took my hand.

“You’ve been pretty tough through this, you know,” he said, and my heart filled.

Sitting on the log reliving that memory after so many years have passed, it comes to me and I snap back into the present: I am not stuck, I am lost—there is an important difference. I need orientation, not extraction. There isn’t anyone here to save me, so I need to do that for myself.

Like Dorothy, I suddenly remember that I have had the answer the whole time and finally pull out the damn map I have been carrying all along but since I wasn’t lost for several hours wandering around the forest, I didn’t need it. I instantly see where I went wrong (wrong creek, wrong drainage), which leads me to see where I am and how to get back. This is all a great relief, but it is still several miles away. Because I have been wandering around for so long, spinning my tires and digging myself in deeper, it is now getting late enough that my husband will be getting worried and thinking about coming to look for me. Without cell service I can’t call him. I begin to worry. If he comes looking, he will start up the main trail that I am not on. I have no way to let him know I am OK. Thinking I could be hurt, he might hike until dark looking for me while I am safe in the parking lot. A rush of feelings from my past and present collide in me: relief at knowing where I am, shame for taking so long to do the things I know to do, panic at the inconvenience my carelessness could cause for other people and bewilderment at how after so many years, my first instinct when something isn’t working out is to convince myself to just keep doing the same thing and it will all work out. It is only when I stop and become quiet that I can see there are other things to try.

Two hours after sitting down with the map and drinking the last of my water, I am sitting in my car. Twenty minutes after that I am sitting on my deck, drinking the most delicious glass of wine as I come clean with my husband, who gently smiles and shakes his head.

Instead of shaming me with should haves and why didn’t yous, he sees that I know them already. Instead, he offers his own story of getting lost, or rather almost getting lost, when he took the lead climbing down with a few buddies and missed the route only to have his friend hale him back, “Hey, Where are you going?”

That is the question for all who are lost or stuck. Where are you going? Why aren’t you getting there? They may keep moving, thinking they are making progress only to find they have gained no ground. Or they may be unable to move forward at all, trapped in their own repetitive patterns, powerless to break free of themselves. Stuck or lost, chances are you were on your way somewhere when you got derailed, and pushing ahead may not be the right answer. Next time maybe I will stop, right there, on a log or in the mud, and acknowledge that maybe I need a little help from an imperfect boyfriend, from a map, from a therapist, from the world, from the part of me that remembers reaching out can actually move you forward.

“I am lost, I am not stuck. I need orientation not extraction.” These words resonate with me. We are so much stronger and capable if we only allow ourselves to let it happen. Thank you so much for sharing this story. ❤️

It feels great to hear this one connected! Thank you, LA, for taking the time to write that.

♥️♥️

Thank you friend!!