“You’re living in your own private Idaho”

“Private Idaho,” The B-52s

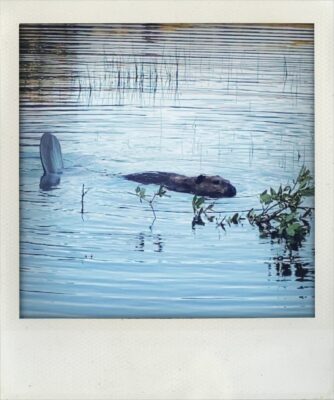

When the first chills of September sidle in, the Grand Mesa Mosquito Association packs up and heads out for the season, allowing visitors to camp, hike, fish and paddle in peace. This blissful period is brief because the Grand Mesa, which is the largest flat top mountain in the world, is one of the first places in Colorado to get snow, and it usually comes mid-month. But for these two weeks or so you can bare your unsprayed skin near the hundreds of lakes with relative comfort.

We are here this weekend because my daughters just became unemployed when the very popular cafe they both worked for closed due to chronic under-staffing, largely the result of extreme housing shortages. At least three of their coworkers had been living in their vehicles, including a Subaru and a Corolla, while others’ housing seemed always on the edge of disappearing. Some folks say that the town runs on high school kids because they at least have housing.

Spend one day as a waitress in a busy restaurant, and it can change you as a customer forever. You will no longer be oblivious to the rude and demanding side of humanity. Resort-town living can give you the same insight. In the eyes of the visitors who aren’t part of the everyday community, residents are a kind of authentic theme park character, like Snow White or a life-sized Minnie Mouse, the ones playing a role that brings the theme park to life for the visitors. You are not a real person, like them, who has errands to run, appointments to make, children to care for, a job to do. Because they paid their price of admission, be it a $28 burger or a $450-a-night hotel room, they now should be treated as treasured guests of the park. They expect to walk wherever they want without regard for cars or other people trying to use sidewalks or streets to get somewhere. They amble with leisure four abreast on the walkway and seem surprised, hurt even, when you pass them at a different pace. On the roads this may look like driving fast on the straightaways, which are like the roads they are used to, but then dropping to 10 MPH below the speed limit on those scary curves, shunning pull outs as the line of cars snaking behind them approaches infinity.

The only time they seem to be in a hurry is when they are at a restaurant. Then they are irritated if there is a wait for a table or their food, because suddenly the theme park operations have infringed on their precious leisure time.

If you get stuck with one of them, say waiting in line or riding the free gondola, they are all a-gush at the beauty of the place, how much they enjoy it, how they are coming back for sure, how maybe they will buy a place so they can vacation here for a few weeks a year. You smile and nod and try not to let your inner fatigue show, which would be out of character. Even though your house is less than 3 miles from town and you are connected by a bike path and a free shuttle, you vow to avoid town during the summer tourist season, and the winter one, too. You think, “I will go to town twice a year, like the mountain men of old, gather provisions for the next six months and retreat back to my tourist-free zone.”

If the reader does not live in a resort town, they may be thinking of this ungrateful author, “You are so naive and hypocritical! Tourism is your economy!”

Yes, I would humbly reply, but it didn’t used to be our culture. Though it may appear like a theme park, we have schools, clubs, hobbies, a town council, housing problems, worker shortages, suicides, rapes, poverty, substance abuse, food shortages, homelessness–all the issues other towns face. In addition, we have evidence of disrespectful guests, like bags of pet waste and toilet paper flowers scattered about on the trails and tundra waiting for “staff” (who don’t exist) to come and clean them up. We have great disparity as 50% of our homes sit vacant waiting for their masters to return, while other people are sleeping in their cars in between restaurant shifts because they can’t find housing.

And, might I mention, without a town’s worth of people who live and need to work in the theme park, there would be no activities, hotels or concessions. We want visitors to realize that, although we know it is beautiful here and we want you to visit, we also want you to realize it is a real town so please don’t act like it’s Fantasy Island and your wish is our command just because, well, without your money where would we be? I might respond, we would get by without you, but without these mountains, you are stuck with a world of sidewalks and buildings and trees planted in sad little squares. It seems to me that the world needs our wild places more than our wild places need the world. So act accordingly. Act like you are in a special sanctified space rather than on Rumspringa in Vegas. Stop leaving your toilet paper flowers and poop bags behind. Be kind and appreciative of the people who are making it possible for you to enjoy your time here, the ones who treat the water and clear the roads and respond to accidents and serve the coffee and shovel the snow and clean the hotel rooms and teach the kids and, and, and.

This is not a new story, though, because places of exemplary natural beauty have always drawn the wealthy, attracted them like lions to the water holes of the Serengeti. And when you are fighting for territory in the modern world, money almost always wins. Almost.

Driving home from our weekend on the Grand Mesa, we read in a brochure from the visitor’s center an anecdote of privatizing wilderness from the 1890s. An English aristocrat named William Radcliffe acquired the title and fishing rights to the Alexander Group of lakes, a prominent cluster among the more than 300 lakes that dot the mesa. Mr. Radcliffe set about improving the hatchery and hotel, counting the fortune he would make off the glorious high altitude spruce forest, pristine lakes and abundant wildlife. He sold permits to his neighbors whose families had been fishing the lakes for free for generations. They didn’t buy the permits. They poached the lakes. Radcliffe retaliated with game wardens, and the tension escalated until a game warden shot and killed a local rancher who was fishing without a permit. When Radcliffe was away, an angry mob burned everything the developer owned, and Radcliffe never returned to Colorado.

The urge to possess may be universally human but seems to be acutely strong in the wealthy elite who gravitate to the mountain resort towns of Colorado. What are they trying to acquire? People who live here all the time have a connection with this place. That’s what it means to have a home. Connection, though, cannot be purchased. It must be developed and that takes a different kind of investment. On some primitive level, I privately applaud those Grand Mesa fishermen from the 1890s. But in my experience, whether it is owning wilderness or traveling to the Moon, what wealthy people want, they usually get. Today there is plenty of private land on the Grand Mesa, but the lakes aren’t. So we could learn from the past and try to find a way to share this place so all the people who love it get what they want and what they need. To compromise. And maybe this time we can do it before someone gets killed.