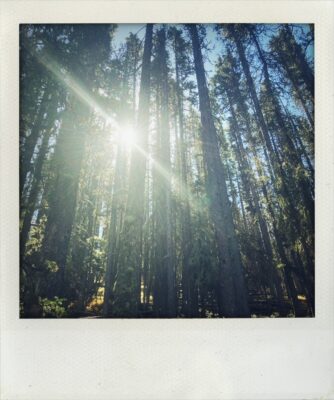

The yellowing aspens and orange underbrush announce fall, and the crisp, clean, airless air is too dry and thin to carry the full rich scent of pine that surrounds me. As the steady rhythm of my footfalls sends trembles through my body, I feel relaxed. There’s a psychological safety in a trail through the wilderness, and this one is tidy and wide. My steps are sound and sure as they hit the packed-earth trail, leaving my senses to wander with my imagination, drunkenly gazing in and through the woods around me. Pencil-thin lodgepole pines stretch towards the sky in Newton-defying heights, creaking in the gentle breeze like loose floorboards. These amazing trees, the ones Native Americans used for tipi poles, I can put my arms around even the tallest ones that are soaring more than 80 feet in the air. Stillness and silence prevail, however, among the wilderness residents, and my hearty breathing seems loud in comparison. The trail slants up and shimmies down. It curves up toward the mountain summit above me then winds down to the bottom land, until all at once it stops.

Completely.

Covering the trail is a 150-foot swath of Mother Earth-birthed renovation and renewal. A river of uprooted trees lies in my way, the debris field of a massive avalanche. A heartbreaking array of evergreens lie prone before me in a tangled mess of mass, rising up to my shoulders in some places.

The swath of downed trees is so broad that neither I nor my hiking partner cannot see where the trail continues on the other side. There is no going around, so I climb up on the first log. It looks vulnerable and submissive, like a surprised corpse, trapped forever reaching after the down-flowing snow that had long since passed. But once inside the horizontal forest, its twigs poke me and its branches block my way. Even castrated and grounded, these trees are still massive and impenetrable.

It takes more than half an hour, but once on the other side, I glance over my shoulder and take in what I am about to leave behind. The force required to level hundreds of trees in an instant is hard to imagine. Colorado ranks highest in avalanche deaths of all states as it has, for the most part, since such records have been kept. It makes me think of the skiers and boarders I know who lost their lives to the power of sliding snow. My community has lost at least a dozen people like that in my time here, and I have known a few of them personally. All of them left behind a swath of pain and loss as broad and hard to imagine as what is before me.

Releasing that somber thought, I realize that, though we are almost on the other side of the avalanche, we don’t see that tidy trail anywhere. We keep threading my way through the trees, thinking that we will pick it up soon, but at least a half-mile passes and there is still no sign of it. I am struck by an image of people driving down a road, stopping for a scenic overlook and then returning to their car to find the road has disappeared. I would like to be a hawk flying overhead to watch that, but if I was, I wouldn’t care much what happened to these folks, and the mountains wouldn’t care either. The deer wouldn’t try to help because there is no “lost” in nature. But we, most certainly, are lost in nature. The trail is gone. We cannot retrace our steps to find the trail nor do we see it around me. I lift my head and look around. The sun is low, casting a buttery light on the forest as it shines through the aspen leaves.

This is my first summer after moving into my cabin in the winter and while I don’t know exactly where I am, my partner and I do know that we are between the mountains and my cabin, which lies below us where two creeks come together. Judging from the placement of the sun, it looks like our cabin is to the northwest, and we head in that general direction, keeping the setting sun to our left. The hiking is painfully slow as we are now bushwacking down the slope, climbing over fallen trees and through deep gorges, nature that was seconds ago a cathedral of my worship and contemplation has turned into an apathetic adversary, thwarting my escape at every turn.

If we head down, there is a drop off of little or no grade, and if we go up, well we really don’t see any damned sense in going up since our whole objective is to get down out of this damned forest before the sun goes down and we are stranded here, him with a pocket knife and a lighter and me with a very pretty scarf (kind of a sultry salmon-and-roasty gold batik). Trees keep nipping my thighs with their forward branches, and the uneven ground seems always to oppose my expectations. I am getting tired, having a hard time keeping up, and I feel my body whine in discomfort with each step. I wish I had worn better shoes.

Late afternoon’s luminous rays reach through the trees with the warmth of a mother’s hug, and I want to sit and rest, to return to my thoughts, which are far less strenuous than taking step after step. But steps are the only option, so I press on because the now orange-gold light tells me darkness is coming, and we must clear the trees before then. Miles cannot be covered quickly in this terrain, but we both trudge on, hoping against reason to find an easier way out of the forest.

As if wishing made it so, a richly grassed aspen grove opens before us, filled with the largest trees I have yet seen. Too big to hug, one has a date upon its papery surface: Bill, 1932. I can’t linger, though I would like to, and we march on. Other than the quietly respirating trees, I feel like we are the only things breathing.

At last, we both see a break in the trees and head for it. My heart quickens with my steps as I reach a clearing until we find a hill instead of a view. Balking and bitching by now, I start the climb up the hill, my legs singing with strain as they fight gravity. I hope that from the top of that hill, we will know where we are, but when we crest, I am utterly deflated by another damn hill. Then, just as suddenly, I am lifted by the sight of eight lovely mule deer. They tilt their heads in surprise, but they aren’t spooked. Probably looking for a soft pasture to bed down in for the night, they just stare and softly stroll on, like sunbathers seeking a better spot on a suddenly crowded beach.

I am worried by the low sun, but I decide to stop and drink some water, nearly our last. My partner finished his an hour ago. It tastes clear and cool. I look around and wonder if we should be looking for a place to spend the night, because we still don’t know where we are. We still have some time, though, and I use my self-inflicted fury for fuel. I am not sure if I am mad because we didn’t try harder to find the trail after the avalanche, or if I am mad at nature, which seems to have swallowed us when we were just passing through. By my own hand or by circumstance, I feel trapped, and I ache to be free and safe and home reading adventure stories instead of living one. Reading has never given me blisters.

We press on, climbing around and over and then I force my rubber legs to do the work of going up yet again. This time, it pays off, and from the top of that hill, in the distance my partner points to an outline of a huge house, one of my neighbors, and for the first time I am glad to see a trophy home breaking the skyline. We know where we are. Even I know how to get home. I just have to walk. He estimates it is almost three miles, but we are on the flat open of the mesa now and can take the road or shortcut it on the grassy hills.

It is fully dark when I trudge heavily up the front steps into the cabin. I land hard in my favorite chair, shaking the silence inside. I feel beat up, sore and relieved—a kind of fear hangover. Everything hurts, and those damn stupid shoes have given me sizable blisters on both heels. My legs are covered in scratches, and my shorts are torn from climbing over trees. I am still kind of stunned by how quickly I went from feeling comfortable on the trail to feeling scared and alone without it. I feel like I entered the wilderness today, maybe for the first time, seeing its power and benevolence. It held me for a while, and then it let me go, changing our relationship forever.

That feeling of safety I had when I started the hike was maybe the same feeling my friends had when they headed out to the backcountry. Neither of us was seeing the wilderness for what it truly is–a natural but also dangerous place. A trail–packed dirt or groomed snow–provides us a way through nature, safe and secure. Once we leave that trail behind, we are in wilderness in the same way the deer and marmot and ground squirrels are. That trail allows us to stop taking the measure of our surroundings, to stop finding our way, to step out of the place we are in and go into our minds, thinking about the fight we had with our boyfriend or what we will make for dinner. Without a trail, we must engage, must notice, must attend. Maybe when I left the comfort of my favorite reading chair that is what I was seeking all along, connection with the true nature of things, and today, it came. I lost the trail and found my way into the wilderness.

What a delight to read these adventures and misadventures of a good long hike in the mountains. It reminds me of the days when I hiked by myself in Southern Utah daylight to dark every chance I got away from my job and my life in Logan’s burbs until I hiked myself right out of a marriage.

I also loved the post before this one of the pink sunset at Toni & Judy’s. I aim to get there and enjoy that retreat one of these years.

Thanks for the rowdy and romantic ruminations,

Star

Thank you Star! I feel like we could fill an evening sharing stories of losing ourselves in wilderness. Toni & Judy’s place is so special. If you make it there, you will leave nourished.