It’s well into autumn, but it’s been warm with no frost yet, so it’s still August as far as some plants are concerned, and they are thriving everywhere in this literal island of floral diversity that makes bedfellows of succulents and ferns and lily pads. We are strolling through Denver’s Botanic Gardens, a lovely wonder that makes a verdant paradise in the middle of high-rise apartments and downtown hustle. My daughter’s dog needs a leg-stretcher, so we grab a coffee and walk to the adjacent Cheesman Park. Expansive and relatively empty, the park has a Greek-style pavilion with a rectangle colonnade (courtesy of the Cheesman family), an empty pond, and large expanses of still-green grass. Exactly what we are looking for. Some people are walking on the outskirts and there are a few other dog owners, but the park is sparsely occupied, which seems odd since it’s Saturday. As rural people, we are more accustomed to rocks and plants than concentrated concrete and are thankful for the space and spaciousness.

“I wonder why there aren’t very many people here,” one daughter asks.

“It would be awesome to live near here,” says the other.

Given Denver’s soaring prosperity—it’s the fastest-growing city in Colorado and the 10th in the nation, per the U.S. Census Bureau—we are all surprised at the general shabbiness of the park. Maybe it is the unfilled pond, maybe it’s the large lawn and lack of overall design that contrasts the strong statement of the weird colonnaded pavilion. Like someone set it down there intending to move it later but just forgot about it.

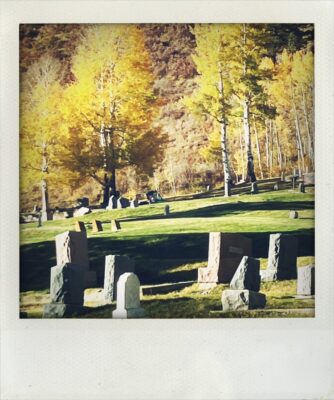

A possible explanation for the odd energy of the park comes a few weeks later when my daughter sends me a Tik Tok about its creepy history. Cheesman Park used to be a cemetery until Denver found the land too valuable for dead-body storage and had the graves “relocated.” According to the Tik Tok guy (and the Denver Public Library) the contractor was paid by the casket, so when the scandal broke open later (you knew it would) bodies were found to have been dismembered in order to fill multiple caskets and increase his payment. This was discovered mid-project, so there could be as many as 2,000 bodies of the original 5,000 still buried in Cheesman Park. Since the millennium, there have been at least a few reports of skeletons unearthed by crews working in the park and in the adjacent Botanic Gardens. Bones have a way of working to the surface.

A BBC article from 2015, “The World is Running Out of Burial Space,” reported that a 2013 survey showed that nearly half of England’s communities could run out of burial space by 2033–that’s less than 10 years away. As if in response to a shortage that could cross the Atlantic, the variety of American burial practices is increasing, too. This could be a space issue, but also could be connected to the declining religious affiliation in Americans (about half say they are religious, down from about 85 percent just 50 years ago). Who knows why, but TIME magazine reported that in 1980, only 10 percent of corpses were cremated. Last year the Cremation Association of North America reported that about 61% percent were cremated–that’s a six-fold increase in 50 years. Of the cremated, the National Funeral Director’s Association says only about half of them have their urns interred. Ashes are far more portable than a casket–you can send them in the mail (but you have to sign for them), so it’s very common for the deceased to leave instructions for special places where their ashes are to be scattered. My mother, an Illinoisan all her life, specified that some of her ashes come to Colorado, a place she visited often after I moved out here. And for some, there is the ocean.

A 2022 L.A. Times article reported on the growing popularity of being buried at sea, which is easier than you might think, more environmentally friendly, cheaper than traditional burial (especially if you live near the coast) and has a lovely reunification resonance to it. A burial facilitator quoted in the article said she hears people say, “… ‘I like the idea of becoming a drop of rain someday.’ ”

Land-loving environmentalists can choose to grow a tree with their own personal carbon in Tree Pod Burials, where the naturally decomposing body nurtures the growth of the tree. Benevolent humanists can donate their bodies to science (pending some limitations). You can even be buried at home. Colorado (and all states but three) allow a person to be buried on their own property.

I went to such a burial a few years ago. The man had spent decades on that piece of land that was his home, and the simple yet powerful ceremony had such a natural and peaceful beauty to it. It made me wonder why this wasn’t more common. This, after all, is how burials were done for a long time in the U.S., particularly the frontier American West: you dug a hole, you conducted a ceremony, and the body was joined with the earth.

Cemetery or sea, science or scattered ashes, it seems the tradition of uniting the dead body with the Earth and its elements is as old as human culture itself. The first indications of ceremonial burial for humans go back 80,000 years. BusinessInsider estimates that for each of the 7.4 billion people alive right now, there are 15 buried people–that is 111 billion people, give or take. For many, uniting their dead bodies with the elements is perfectly fine, but many cultures hold the tradition of keeping cemeteries separate. That sets people apart from nearly all other life forms whose deaths participate in the cycle of surrendering to unsung scavengers and legions of mycelium that spend their days turning death into life. In truth, death is all around us and, in the fall, we even drive miles to revel in its beauty as leaves depart branches to die on the ground, hallowed or otherwise.

The blurring of death and life reminds me of something a friend shared with me recently. She was talking with her dad about visiting her mother’s grave, when her dad said unexpectedly, “Focus on the living. The dead are always with us.” This resonates with me, but I also understand that for some mourners, the sanctity of a sacred site where they can visit a loved one is revered, necessary even. Millions of people across the country visit cemeteries to soothe their souls and attend the deeper missing. There is so little solace available to one walking through grief. If a cemetery serves that purpose for the living, it may have earned its space.

Still, there is only so much ground. As urban populations grow, historic cemeteries can become transformed into treasured open space, like Cheesman Park in Denver or in Queens, where the Newton Cemetery was converted to a park in 1927 when the city did not attempt to relocate anything. Instead, they simply laid the headstones flat, covered them with soil and put a park on top. As we throw the ball in Cheesman and watch the dog bound over green grass and maybe hundreds of bodies, I am struck by that image of transformation, and all that death and life commingled just feels right.

i didn’t know that about Cheeseman Park! Wow!

all that death and life commingled …

Yes! Just like the leaves beneath our feet. Loved hearing you last night. Elecric!! I started reading your new book, The Unfolding. It is so, so good!!

Lots to chew on here. It was like revisiting that great Mary Roach exploration, Stiff, where she describes all the ways we decide the fate of human cadavers. But with more compassion.

My favorite quote: “Focus on the living. The dead are always with us.”

Thank you, Star! I think about that one a lot, too. I will have to check out Stiff. Sounds compelling.