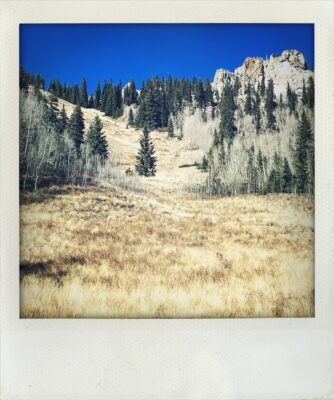

Even though dawn is less than an hour away, it is black dark, clear and cold, the stars vibrant crystal lights. Coyotes split the silence, first with their laughing cries then with a clear, long-noted song I have not heard before. We wait for them to finish and then start up the trail with headlamps, though soon we can navigate by the low slinking light of morning. The trail is mostly clear, but now and then we slip on carpets of leaves and patches of new snow that make a leopard print of the creek bank. Our grunts when we do are the only vocal sounds we make. Ground is covered slowly, and there is much to gain before we get to the small open meadow where we hope the elk will be.

At first I work to be quiet and stealthy, but the terrain is unforgiving and I find that I can either be silent or cover ground, and we need to cover ground. I am much slower than the hunter, but he waits patiently for me just ahead, close enough that I can see his orange cap. It takes us more than an hour to reach the golden grassy field.

Just before exiting the cover of the creekside willows, we talk through a plan that considers if the elk are there, because we don’t want to spook them. The hunter goes ahead. Now it is more important to be silent, and I move so slowly it is mildly irritating. When I finally get in sight of the field, there are no elk there, only the hunter, looking around, contemplating.

At the open field, we are in the sun now and welcome the warmth. Sitting in the dead and dying grass we figure out what to do next. It is Sunday. We have to work tomorrow, and both of our daughters need our help. One is on crutches and the other, who is away at college, has a seizure condition that is flaring up. The call of the hunt faces off against the pull of life.

The hunter finally says, “Well, it’s the last day of the season, and since we’re here, I think I should hike up to that bench above us. They could be up there.”

I agree and offer that when we hike out we can decide who will help which daughter. Hunting, I am learning, doesn’t heed the march of the clock, but moves in a different seasonal time that is marked by weather and forage. It is a maddening mix of move and wait; be calm but always ready. The hunter enters this state easily. Maybe he is always in this state. I find it difficult to be attentive and relaxed. As soon as I stop moving and settle in, my mind wants to return to its meal of worrying about my children, contemplating life changes, wondering about that coyote cry from this morning–what was that? This drifting out of my environment is why I am so shocked when, before he has left to hike up to the bench, the hunter quietly but with command says, “elk!” and in seconds I hear a loud cracking shot. It all happens so quickly it seems to have manipulated time somehow.

I, of course, am facing the wrong way, gazing across at the peaks catching sun where there are no elk. I turn around just in time to see a line of elk crossing the chute about 300 yards above us. Though he missed the first elk, who is in the trees now, his shot made the herd speed up from a walk to a trot. Methodically but lightning fast, the hunter adjusts, sets up his shooting sticks, and is able to get the third elk crossing the field just before it heads into the trees. She falls instantly. My chest heaves, and I release a bellowing sob from a deep place I have just discovered. A place where she and I are kin.

The shot hits her in the pelvis, and she begins to jelly roll down the steep hillside. This is painful to watch and unfolds slowly, in sharp contrast to the rapid fire events of the last few minutes. She tries to stand, and the hunter positions to take a kill shot and end her suffering, but before he can, she falls again below the cover of grass. Meanwhile, the birds who have been watching us from the perimeter have closed in. A magpie flies directly to the cow, who is still alive and screams at the bird, making a sound the hunter later will say he has not heard elk make before. After raging at the magpie that she is not dead, the elk stands again, this time long enough for the hunter to end her life.

The hunter is two people now-human and hunter—and the hunter is in charge, moving by practice and ritual to the next steps of gathering his tools to gut and skin this cow that will feed us for the next year. I am two people, too, human and observer, and what I have just witnessed calls up my human to his. I go to him, the need to hold him strong in the overwhelming emotion of this moment. He stops for me, reluctantly at first, then fully as I feel his entire body pulsating with energy, adrenaline probably, but scientific terms deconstruct the moment too much. The energy that is moving through him is ancient and unnameable in its wholeness. To sustain our lives, he has just taken a life, a wild and precious one, and there are deep and conflicting emotions in that act. We hold each other until the vibrations of his body diminish somewhat. This will be the only pause in a day-long sequence of difficult tasks. We walk up to the elk.

When we reach her, she is still warm but lifeless, and we both drop to the ground sobbing at the sight. She is a big cow, and a quick look in her mouth reveals worn and flattened ivories suggesting she is old. It comforts us both that maybe she has been spared what might have been a hard winter. We take a moment with her and express our gratitude in our own ways, out loud and silently. Then the work begins that I am not a part of. Dressing out an animal—an odd term since you are quite literally doing the opposite down to removing the skin—is not only physically demanding but precise in both order and execution. His first priority is to remove parts that can damage the meat, and he goes to the neck to cut away the windpipe. I am struck by how it looks just like home heating air tubes, a membrane around a thick coil of cord. Then, for the better part of an hour, he detaches the guts, moving his knife largely by feel, as he works its way between the hide and the organs, careful to not pierce any of the soft internal tissue. The physicality of this task is significant, and I am able to help only by holding a leg just so or adjusting the carcass.

I know that internal organs are all connected, yet still I am surprised when at last he is able to pull the entire insides of the elk out in one massive bundle. It strikes me how separable something is that I think of as one body. In the end, all mammals are skin, muscles, and bone; digestion, breath and brain. What a machine–so simple yet one that we radically complicate with the extraneous nonsense that is human culture. I wonder if hunters have this same realization every time they field dress an animal or doctors at every surgery. Why can’t life be as simple as feed and water it, work it and keep it sheltered from extreme temperatures?

Though we are still tender with the emotions of the day, the work and warm sun dulls our feelings with fatigue from the extensive effort. Once the organs are removed and the hide is cut away, which the hunter will take, what remains is bone and muscle, which is now meat. Quartered into hinds and fronts, the meat, including the choicest cuts that run along the spine, will be bagged and packed out by a stronger person than myself. I will carry everything that will fit in my pack and the rifle.

As we prepare to leave for the first of a few trips down to the car to pack out the animal, meat stored in game bags is taken to snowy spots in the shade. The elk has started to stiffen from rigor mortis, and I am surprised this has happened so quickly. Scavenger birds of all kinds—magpies, ravens, crows and even camp robbers—shuffle restlessly between the branches of nearby trees waiting for us to leave. Before we do, we take a last moment, and the hunter completes a ritual he has done with every game animal he has killed.

I watch as he reorients the elk, placing the body angularly on the slope facing away from the afternoon sun. He searches to collect some late-season still-green grasses from the southwest facing slope, takes my hand, and leads me to the cow. The sun is strong now and we have shed our coats. It is calm and the late afternoon light bathes us in a hearthen honeyed glow as we walk across the steep slope.

“Mouth full of grass, facing east,” he says as he fulfills that promise, placing the elk’s head to face the rising sun and filling its mouth with the freshly picked grass. I don’t know if other hunters have rituals like this after killing an animal, but this one does. My chest tightens with a mix of sorrow and gratitude, thankful for this ceremonial act’s respectful closure to the hunt. We head down the hillside, this time on a trail.

On the walk down I feel a brew of emotions. Grief for the elk, relief for the hunter, and also pierced by how this natural and ancient act connects me with humanity back to its origins. So little of my everyday life is spent meeting my basic needs the way humans have for millennia, and this holds me. On the walk back to the car I feel suspended between the world of the elk that has always been and the one humans have made.

I think about this cow who was in the final chapters of her life. My back molars have caps on them and I am older now, too. In the last few years, I have lost three friends my age—in their 50s—and it has shaken me. I feel that I have much more life ahead, but these losses make me aware that I can never know how much. Since life is made of only time, that is what I think about as I make my way down. I remember how the days stretched out when I was young. My teenager just lounges sometimes for hours and I watch her in slight annoyance until a deep memory surfaces: Oh yeah, I used to do that, too. That was before the days filled with work and hobbies and kids and other people until they became so compressed they were difficult to enjoy.

I noticed this during a particularly grumpy few years when my kids were in their early-middle teens. Days just spun by and I felt consumed by them until we made a change and moved to a smaller place closer to work. I reduced the commute, gave away many of my possessions and winnowed my commitments until I felt like I could breathe again. I remember watching truckload after truckload of stuff leave, and instead of feeling sad, I felt myself grow lighter, younger even. By the time I was settled in my new home, I had a spacious existence and instead of cluttering up my new house and life, I committed to the spaciousness. Now I do not say, “I am so busy” because I am not. I also never say, “I am bored,” because I am not. When I start to feel myself moving toward either extreme of activity or inertia, I look at my diet.

Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hahn helped me understand this relationship through how he talks about the “food of life” in his book, How to Love. You would not think a tiny book on love would have much to say about food, but in his eyes, it is all food, or rather, it is all love. He explains that, “Everything needs food to live, even love. If we don’t know how to nourish our love, it withers.” He shares the big secret that, when we feed and support our own happiness, we are nourishing our ability to love. As a Buddhist, he sees everything as connected and alive, and the purpose of being alive is to grow. In order to grow, we need to be fed, and there are four kinds of food: edible, sensory, volition and consciousness.

Edible is straightforward, and he has an entire book, “How to Eat,” where he helps us connect more deeply with what we put in our mouth. But what about what we put in our minds? Our hearts? He tells us that our sensory food–what we see and hear–also feeds us. The shows we watch, the books we read, the conversations we have, the media we guzzle–all of this is food. Before we consume it we should ask, what is it feeding: fear, anger, resentment and righteousness? Or inspiration, gratitude, compassion and connection?

To think that the food we eat is only one of many ways we feed ourselves is a thing to ponder, and I realize that is how my life became spacious. I started noticing which things I was doing that fed my dark feelings of burden or resentment. Which is not to say I am oblivious to the wrongs of the world–compassion literally means to suffer with, and that is an essential function of love. Rather I started trying to feed my happiness. Still, after streamlining my life and nourishing my joy, when I die, will I have such a simple recipe for happiness as a mouth full of grass, facing the morning sun? Are my sources of happiness the bounty that exists around me or have I made happiness a thing that is always just out of reach?

As we come to the first clearing about half-way down the slope, I look back toward the meadow where we spent this day. I see the magpies and other birds diving and rising from the clearing we just left, turning loss into gain, death into life.

Beautifully written!

Thank you for that!