for the bookstore

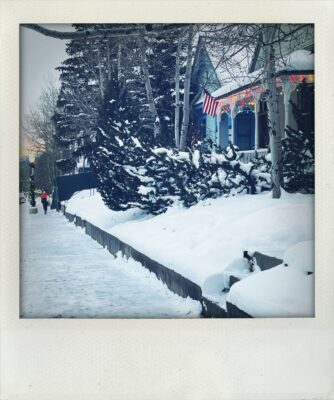

It is an unbeatable winter setting—snow falling softly on quaint Victorian homes and globed street lamps, mountains looking on in the background. The opening scene of any given Hallmark holiday movie could have been filmed in so many Colorado mountain towns made cozy by historic homes snuggled together amidst golden lights and evergreen garland.

It doesn’t matter how many times over decades and seasons I have seen these mountain towns, including my own, to me they look the most magical in winter. Is it the alpine setting that conjures enchantment? Maybe it’s the Dickensian aura of the lampposts and Victorian houses. Or is it Hallmark I have to thank for the impossibly hopeful and sentimental feeling I get from this place in winter?

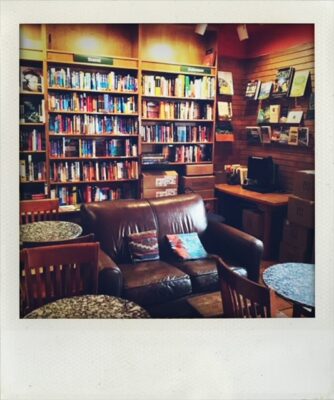

Of course, that romantic glow is not infallible. Soon I am driving slower than a snail, dodging inattentive pedestrians and unpredictable out-of-state drivers as I look for a nonexistent parking spot. After 20 minutes, I finally fight the thick snow and squeeze into a space for just two bucks an hour. I grab my bag and head to the last remaining local coffee shop; the same one I have been going to since I moved here decades ago. It is tucked in the back of the only bookstore in town, one that has been open in the same location since 1974. For a moment, my Hallmark feeling is restored by the roasty smell of coffee, the sight of towering wooden shelves filled with books, and the creaking sound of uneven hardwood floors, a signature of these historic buildings. I feel a surge of warm joy as I browse my way back to the coffee shop, where my glow is quickly extinguished by the surly barista.

“Hi there. Can I have a drip coffee for here?” I ask.

“Do you mean in a mug?” she asks me, looking inexplicably annoyed.

“Yes, please,” I say, feeling like an imposition.

She looks past me, still with that irritated expression, and says, “We’re not really doing that anymore.”

It is 3 pm; the coffee shop closes at 5 pm. I am taken aback by her tone and unsure what she means by, “We’re not really doing that anymore.” Even though I do not want to drink my $4 drip coffee out of a paper cup while I sit on the luxurious leather chairs or at the marble table, my compulsively compromising Midwesterner blurts out, “Or a to-go cup–whatever is fine.”

Both of my kids have worked service industry jobs in a ski town, and it can be brutal. You would think that people on vacation in a Hallmark village would be bubbling over with happiness–and many are–but not a small number of them are flat out horrible–demanding, impatient, rude or inappropriate. In an attempt to balance the scales, I tend to overcompensate and be painfully nice to anyone behind a counter, even when they aren’t.

“And when it’s gone, it’s gone,” she adds, another non sequitur. The coffee? The ceramic mugs? Her patience?

I get my drip coffee in a mug after all, and it is so delicious that I begin to have the Hallmark feelings again as I turn to my journal. I am no less or more romantic than the next person, but I have concluded from an unscientific poll of the people I have asked about this matter that there are two clear camps when it comes to Hallmark movies: one that thinks they are mindless soulsucking drivel and one that finds them binge-worthy feel-good wonders. Circulating lately has been the Hallmark Christmas Movie Plot Generator (included here for your enjoyment) that does sum them up.

I don’t think I am in a camp, so as a research project, I binge watch a tidy 10 Hallmark-style holiday movies, and at the end of each one I do feel better, like I have just seen a makeover show that has set right the wrongs of the world a few lives at a time with only snowfall, nature and small town charm.

Modern mountain towns have many flaws–lack of affordable housing, deteriorating community, imbalance of wealth, lack of diversity, a high suicide rate–but I think there also is still magic in the mountains. I see it in the way people feel they can be free here, whether just for their vacation or as a fresh start in life.

I find out half way through my mug that the coffee shop and bookstore are moving next door and will be closed for a month or so to make the transition, which sheds light on some of the exchange with the barista. I hold the warm ceramic with both hands, savoring the last cup of coffee I will ever have in this spot, nearly 30 years after my first.

As I hold my mug, I imagine how much this bookstore has seen since it opened in the 1970s, when the first groups of misfits gathered in this very spot. Before the ski area opened in 1972, around 600 people lived in this town of mostly decrepit buildings, few jobs and marginal roads. Other than skiing, what towns like these could offer newcomers was refuge from a nation whose culture was being forever altered by the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights movement. In the mountains–then and now–seekers found solace from mainstream society. For some, that was a new beginning. For others, it was a lifeline.

Even when I moved here in the 1990s, there were still many such outcast characters around. Some were “woodsies,” people living in tents in the nearby national forest or teepees or abandoned Forest Service cabins, while others lived in campers or cabins on the mesas. Where or how they lived was unimportant; they were integrated into the fabric of the community. Lots of people were known by first names or, if their first name was common it would gain a modifier, like Steve became Crazy Steve, Shut Up Steve, Baker Steve, Steve-O. The more fringe folks you wouldn’t see as often and maybe cross paths with them in a few places: the grocery store, the post office, the bar or the bookstore.

After the ski area opened, people started coming, and they all came from somewhere else where they had a past they were leaving behind. Among the first wave were college educated idealists, societal dropouts and Vietnam vets. This new stew created an acceptance of newcomers because, well, that was pretty much everyone. It was little different in the mining days of the late 1800s, when most of these places were settled by people who left everything that was familiar to start over in a picturesque mountain town where they could retreat from their triggers, reinvent themselves, or reboot their lives.

I am no different, and I clearly remember both the disorientation and delight of being liberated from my life. Living in the mountains—especially remote and rugged ones—sets people apart, and we embraced that. I wonder, though, is it our true inner selves that are set free by the mountain town magic or is it that we remake ourselves anew molded from the landscape around us?

In the Hallmark holiday movies, the main character finds themselves in an untenable situation and then experiences an unexpected event that causes that situation to unravel. This leads to a resolution in which the main character ends up in a better, truer place. Watching the stories, one after the other, I notice that what drives the untenable situation is nearly always main character’s inauthenticity, and in each resolution they are liberated (or forced) to embrace who they truly are: a city person who prefers country life, a corporate type who would rather run a bookstore or maybe a bitter pessimist who rediscovers belief in love. It is the ultimate makeover story where the unseen hand of the universe intervenes when we have made a mess of our lives, when we have lost track of who we are and what we truly want, which in this cinematic universe is to be ourselves, discover our community and find true love. However, at least according to Hallmark, being yourself really has to come first.

When I think of the outcast characters I have met over the years of living here, most of whom have been priced out or pushed out by now, I think their Hallmark movie might look a bit different. For example, a Vietnam vet with PTSD, triggered by urban sounds and concentrations of people flees the big city after almost killing a person who accidentally bumped into him on the street. Afraid of what he might do, he hits the road with his backpack and hitchhikes to a scruffy town in the middle of remote mountains where a small group of fellow misfits is happy to let a brother be.

He uses his wilderness survival skills to build a small shelter in the national forest where the silent nights and starry skies allow him to have his first full night’s sleep in years. His nervous system finally calms enough that he can maybe even smile once in a while, or open his heart to a stray dog, who is also alone. The closing shot shows our vet, hair ratty, clothes worn and dirty, large backpack at his side, smiling over a steaming cup of hot coffee the barista gave him on the house. He sits, looking warm, next to a crackling fire, dog nearby, its head propped with impossible cuteness on the vet’s knee. He has some peace at last.

We are not all misfits or outcasts or misanthropists, we who have been drawn to mountain towns, especially not now. But to come to a remote place is to accept that you had to leave some things behind, things that may have defined you, for better or worse. In the absence of those things–and the presence of an accepting collection of quirky characters–your true self had a chance to emerge. What you may have left behind were a ladder of ambition to climb, a self defined by others, and a person you may never meet again.

oh how I love this look at Telluride–the perspective of both insider and outsider, the many versions of the movies that could be made here, or missed here … the best ladder to climb in town is definitely the one in the old bookstore.