I don’t always listen to the woods around me when I hike.

Sure, I hear the humph of my shoes hitting the hard dirt,

and, of course, the slurpy gushing gurgle of the creek as I cross it on twin logs.

But I don’t always hear the river rushing a few hundred feet below

or the flap of the Stellar blue jay’s wings against the spruce needles

looking for just the right branch to watch me from

and not be seen.

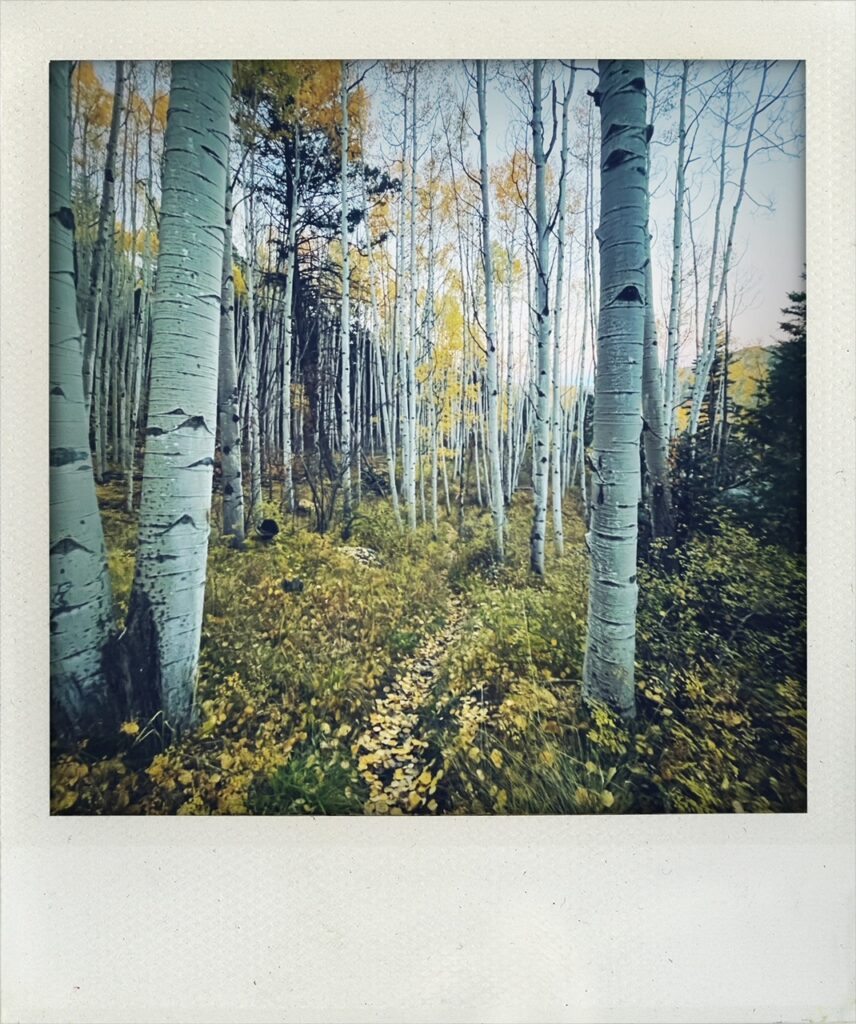

I don’t always hear the gentle tickety click of the dry aspen leaves

bumping shoulders as they are lifted and turned by the light fall breeze

or the whine of hard-working gears pulling a semi up the long hill

bringing more to the mansions on high.

or the faint mid-tone call in the distance

that could be so many things.

On more hikes than I want to admit,

my body moves steadily forward along the trail

while my mind is elsewhere

pondering ideas

engrossed in a book

stuck on a stupid song

replaying the fight with my husband

to find how I am not wrong

only to discover that I have missed entire

sections of the trail,

sections of time and place that were known

only by my body,

my mind gone,

like the deer who flees from habit

even when there is no danger.

Mind is the issue, after all,

how it commands my attention

controls how my sentience and perception work together

or don’t.

Can the I that has a mind and has a body

unite them in a common purpose?

If I listen, can I hear what the forest is trying to tell me?

Do I even speak its language?

If I listen, will it talk to me in a way I can understand

the way the smell of cinnamon talks to my hunger

the way the sun talks to the sunflowers

the way rivers talk to fish

the way my heart talks to the sound of “Mom”

the way my body talks to my husband’s touch?

I will never know unless

I can persuade my mind to stay as it starts to run,

make it feel safe,

tuck it back in my body,

and listen.