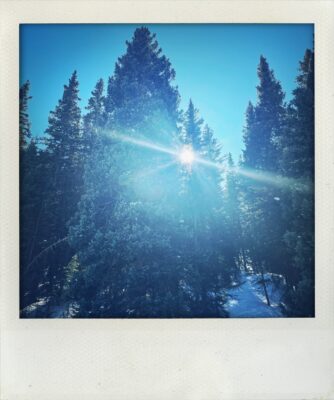

My skis slide easily on the solid snow of mid-winter, and as I push through the forest, I look for one. I don’t usually look for them, in fact I never have before in the last many winters, but this time I do. I think I see her many times, “that one there,” I say to myself, marveling at the soaring height of the Engelmann, its straggly branches 20 times me at least. As I come around the corner I see, great as God, a Colorado Blue Spruce the size of a two-story building, full and broad with age and wisdom.

Could this be a Mother Tree? I have just read Suzane Simard’s book Finding the Mother Tree, and set out today to find one in a forest where I ski. I know that I have seen them before hiking around, usually on one of my husband’s “shortcuts” where we end up bushwacking off trail. Since I habitually hike head down, he is usually the one to say, “Whoah! Look at this guy!” and I will look up to see a tree that is so much larger than anything around that it startles you, as much as a planted thing can. Today though, as I move through the forest alone, my mantra is “look up,” as I scout the dense spruce forest for a tree that stands out, one that could be a Mother Tree.

In her book, Simard recounts how her research on logging practices while working for the Canadian Forest Service led her to discover the complex relationship trees have with each other, other plants (especially fungi) and the soil of the forest. Before her, the established view of forestry was one of competition–to get more of one tree, you removed all other competing trees. Though this practice is still the dominant one today, Simard found that many of the newly planted trees didn’t grow well. To answer the question of why some of the saplings didn’t thrive in the competition-free forest, Simard began a long journey to a greater understanding of how forests work. In simple terms, by studying a healthy forest and mapping the underground fungal growth, she discovered that all the trees were connected through mycorrhizal networks. The biggest and oldest trees were the most connected and were acting as “hubs” in these networks. Seedlings and saplings all tapped into this network to receive extra carbon or nitrogen to help them develop when their leaves or needles were few. This nurturing behavior gave rise to the concept of a Mother Trees, the ones best able to communicate with the saplings around them, send more carbon to ones in need and thereby foster greater success of the new trees. She also discovered that connections between trees viewed as competing species were often beneficial in fighting disease and insect infestation. This view, somehow novel and yet completely natural, shows that in addition to competition, communication and cooperation yield the healthiest environments. That these elements are the cornerstone of a thriving human world does not escape me, and I now look at the forest in a new way, like it just came alive and started talking to me. I almost feel like an interloper as I swish through.

With me nordic skiing in the forest on a Monday afternoon are many other grey-haired folks, some whizzing by on skate skis, others slow as molasses on their classics taking one careful glide after another–all smiling under the unusually warm sun making the mid-winter day mild and welcoming. Seeing them so happy and fit in their later years, I wonder if our culture has any Mother Trees, elders who have abundant resources and wisdom and are using them to successfully nurture our youth? And if we do, what does our version of a Mother Tree look like?

If statistics tell a story, the well-being of American youth could be better. According to the Centers for Disease Control report on U.S. teens in 2021, 42% said they regularly felt sad or hopeless while 22% had seriously considered suicide and 10% had actually attempted it.The CDC also reported in 2021 that 31% of high school students reported current use of any tobacco product, alcohol, marijuana or misuse of prescribed opiates. What do our youth need that they are not getting?

Mother Trees, Simard shares, do favor their genetic relatives, but the interdependence of other species and the overall wellness of the forest makes the relationships multi-pronged and complex. It is not just a direct transfer of carbon wealth, because the vitality of the overall environment is crucial for the success of the individual trees.

Public school is one of the ways our culture supports all children, but as secondary school ends, there is a stunning lack of options for young Americans: it seems like it is either college, the military, a handful of vocational certificates or good luck, buddy. In my news feed, I read about how many graduates, including one of my own, are uncertain about the very college pipeline I followed as a high school graduate. Military enrollment also is declining, both for lack of interest (almost half of what it was in 1985) and rising disqualification, primarily for obesity, drug use and mental health issues. In response, a group of educators near Colorado Springs are trying to build an “education park” to explore vocational and certificate training. I remember studying abroad in Europe during college and being amazed by how many pathways there were for young adults there through apprenticeships in almost any field you can think of. It heartens me that they are calling the new vocational campus a park, which conjures an open space where everyone is welcome to come and get what they need to go back into the world at large.

That college-or-bust mindset of the mid-to-late 20th century has left our country with alarming shortages in many essential occupations—education, medicine, and all the trades—as well as a generation of educated but indebted and displaced people, many of whom are utterly unfulfilled in their work. This move to create an education park, though, is an example of elders listening to student’s and meeting their needs. The competition model, which you could say is the cornerstone of the American economy, is one in which college has long been held as a ticket to economic security. But now we are seeing hosts of shiny new college graduates (at least some of whom really didn’t want to go), drowning in debt, working retail or administrative jobs that don’t pay much and employing very little of their expensive education. No wonder they are tuning out older voices telling kids what they should do “to win” without considering the larger conversation: people want purpose, society has needs. What if our elders started trying to help put those two together?

I marvel at how Mother Trees communicate with their environment through the fungal networks and are instrumental in both supporting their offspring and the ecosystem in which they all live. As complex as forest biology is, it seems the trees, if left alone, have it figured out. This is so different from our modern societal challenges that we are constantly trying to solve and never quite getting there. As the years of new- watching roll by, it seems social problem solving is a perpetual game of whack-a-mole, where solving one creates another, if it even solves the first one. Have we ever, I wonder, had a human version of an old growth forest–a vigorous, happy society that lived more or less in harmony with the natural environment? Not one without death, disease, and conflict, but rather one that achieved some kind of balance where communication, coordination and competition ensured some kind of overall well-being.

A recipe for individual human health can be found with a five-minute internet search: move often, drink water, sleep enough, develop a spiritual practice, have life purpose, nurture relationships, work (but not too much), earn a decent wage, buy less stuff, have a hobby, minimize stress and eat whole foods, mostly plants, not too much. But if you are looking for communities of people doing these things, the only ones I have heard of are those studied by Dan Buettner in his Blue Zones research. In short, Buettner has located pockets of people who, by comparison to the rest of us, enjoy longer, healthier and happier lives. Like extracting Vitamin D from sunshine, his findings sketch out a life that we can do individually or even in small groups, but cannot seem to replicate on any scale: at the forest-size view, it all goes awry. Socialism, capitalism, communism, dictatorships, oligarchies, patriarchies, democracies–there are so many systems of human societies, and none seem to really work. Why are we the only social beings who can’t seem to get the social right, and even choose what is wrong for us, get lousy results, and pick that same option again?

The sun shines through the grand spruce tree like a heartbeat, pulsing with a lovelight wisdom that comforts me, even if I can’t translate it into a language I understand. I breathe in the snow-flavored air and imagine the evergreen scent that is dormant just now but will be rich in the spring. I ski on.

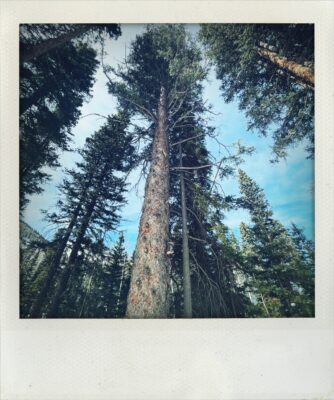

On my way back, I see another tree I had not noticed before. It is straggly and many of its lower branches have been cut. It is very tall, but what I notice this time is its enormous base, the broadest I have seen by far today on the trail, but somehow I missed it. Maybe because I was looking for a fulsomely branched tree that someone would want to paint; that I wanted to photograph. I was not looking for trees with scarred bark and missing branches. I want to see how old this tree is, and employ a formula of the diameter times a growth multiplier (each tree has its own). I try to hug this tree but cannot even get half-way around. By the measure of my reach, I estimate this tree is almost 200 years old, and honestly, it looks like it.

Of course a Mother Tree would be beat-up and battle-scarred from all it has been through: years of drought and dreaded beetles, careless campers and greedy loggers. And yet right next to her is a relatively slender sapling of an Engelmann she may be fostering. Despite what this tree has been through and seen since around 1824, including a parade of people from semi-nomadic natives to GPS-loving luxury campers, she has not lost focus of her job: to support herself, her forest and all the life in it.

well that made me cry … beautiful last lines! And what a powerful parallel you draw. Yes. How do we support our kids, each other? How do we foster connection, possibility, and that glorious short list of ways to thrive? Your words are taking root in me.

Thank you for that, Rosemerry.

In spite of careworn, straggling inconsiderate times the Mother Tree is the Medicine for us all!! The medicine as you poetically say one of communication and cooperation!! Thank You

Thank you for those lovely words!