“The true heart of a place does not come in a week’s vacation. To know it well, as Mary Austin wrote, one must ‘wait its occasions’—follow full seasons and cycles, a retreating snowpack, a six year drought, a ponderosa pine eating up a porch.” —Ellen Meloy, The Anthropology of Turquoise

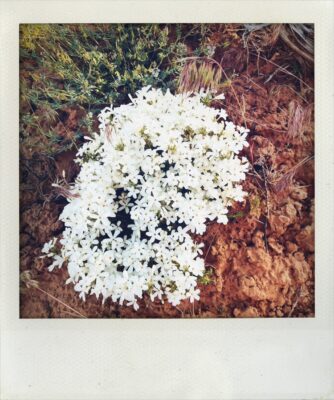

It is the end of May, Memorial Day Weekend, and the weather at 6,000 feet is glorious. Blue sky meets red dirt and green juniper in a quilt of color, dotted by wildflowers at every turn. Hot pink on the hedgehog cactus and ruby red on the Kingcup offer the brightest colors, but the bouquet of white granite gila–closed tightly during the day and opening in the cool night to release its sweet stringent scent–are beguiling all on their own. It is calm and warm, but not too hot. Just perfect.

Even better, I don’t have to share it. In this small, somehow forgotten corner of Colorado, it is utterly without other people. The blissful weather enhanced by the solitude, releases a relaxation in me I was unaware I had not been attaining. Like falling asleep, calm comes by degrees. When I leave the highway and turn onto the county road, there is a deep exhale. Turning onto the dirt road through the trees, my car slows and I along with it. By the time I arrive at the cabin, I have left many layers of life behind, tuning out to do lists and other trappings. Unpacking the food, water and clothing I have brought takes little time and soon I am sitting on the canyon rim soaking it all in. I feel myself drop another level into being, as if it were a place inside me, and maybe it is. By this time tomorrow, I will notice other changes. I will talk less and walk more. I will think less and notice more. I will feel time shift from numbers on a clock to the position of the sun and changing light. I will not want to leave.

This kind of camping is not for everyone. In fact, it is not for most people. If you have never turned off and tuned out for any length of time it can be disorienting. Many, probably most, people grow restless and bored with no scheduled activity, no agenda, no purpose. Some will pull out a bluetooth speaker and play music or chat continuously, preferring that to the gentle coo of mourning doves and bright finch melodies. They might walk through the endless sea of juniper and sage thinking it is monotonous, but if only they looked more closely they would see the artistry in every twisted trunk, how the irregular branches curve and claw their way into the future. I see in that gnarled perseverance the stubborn creativity all things need to survive in the desert’s desolate ecosystem. And these are survivors–many of the Utah junipers could be 500 years old.

Walking through this desert landscape reminds me of a giant library, overwhelming in its possibilities for adventure and exploration. At first, the sheer quantity of contents shuts me down. When my nervous system recovers, a tiny plant or towering tree, like each book on a shelf, reveals itself to have a deeper and richer story to tell. It’s easy to miss, though. To walk in, look at all the books, and if there is no librarian there to single one out as worth reading, turn around and say, “Nothing to see here.”

That’s why libraries and wilderness are, on the whole, quieter places. But wilderness isn’t a library. It is merely a wild place that offers you a choice: you can embrace and enter, like you would a church or a movie theater or a library, opening yourself to what it has to give you, or it can serve as a green screen background for your own life that you brought with you.

The national parks, in my experience, are a gateway to wilderness, a pressurizing chamber. There is a visitor center that provides some information about the nature and culture you can see in the park. You will be directed to trails or overlooks where you can see as little or as much as you want. This map to the park, however, is not exactly like a museum exhibit guide in the sense that if you go to a certain overlook, you will see the rock formation (which doesn’t move) but may or may not see the bighorn sheep that do.

This sounds like common sense, but many people become disappointed and frustrated when a National Park doesn’t deliver on its natural wonders. Artist Amber Share turned one-star Yelp reviews into a series of vintage looking posters on Instagram @subparkparks). For the Grand Canyon, “A hole. A very large hole.” For Yosemite, “Trees block view and there are too many gray rocks.” For Grand Teton, “All I saw was a lake, some mountains and some trees.” Farandwide.com shares this one about the Everglades National Park–the largest subtropical wilderness in the U.S. “Keep it moving folks … Nothing to see here. There’s actually nothing to see.”

Actually, though, I used to be one of these people. When I first moved to dry, brown southwestern Colorado from the lush Midwest, the forested alpine mountains were easy to love, but not the desert. It was like a romantic comedy where the lead actress falls for the classically handsome but cold leading man while overlooking his kind and big-hearted best friend. I saw beauty in the vastness and the red rock canyons, but in a distant, drive-by kind of way. I wasn’t drawn to spend any time there exploring. Until I moved to where the cactus bloom.

Sandwiched in between the sage shrubland and the montane zone, I spent a few decades living in the foothills zone, a transition zone, so to speak, between the mountains and the desert. We had a Ponderosa pine and a reluctant aspen, but we also had pinion and juniper and, for the first time, cactus. What a wonder to watch the Kingcup burst into ruby red blooms or the prickly pear open its delicate lemon yellow flowers. I began to realize how much there was to see in the desert.

Over time I grew to deeply love the ecosystem of the Upper Sonoran zone, where the cliffrose and sagebrush sprout among the Utah juniper and pinyon pine; the land of desolation and discovery. Looking closely, you see the tender fluorescent lichen and the inevitable cryptobiotic soil. If you are lucky enough to walk around with an archaeologist, as we are on this fine day, even more can be revealed.

“This was probably a prehistoric camp site,” the archaeologist says, pointing to a section where gray earth poked through the prevailing cinnamon toned earth. “See how this area is all covered with this fine brown soft dirt. This is called loess, and it is wind-derived and deposited here over eons. It’s mineral rich and holds moisture well. That is why the early indigenous farmers were able to grow crops and how they can dryland farm even now. But this grey dirt is a different color. And where did these rocks come from? They are different from everything else around here. It was probably a fire pit.”

In a moment a landscape I thought was uniform became particular, in the way that a pointillist painting goes from a collection of dots to an image. I am no stranger to wild places, have camped in this area and walked it many times, and easily notice tracks and scat and artifacts like pot sherds and lithic chips. Today I was shown how much I do not see.

“Anytime you see a collection of rocks on top of the loess, someone put them there.”

He makes it sound so obvious.

We continue walking the land with him as he points out features, continuously making things visible I had never seen.

“Over there is a reservoir,” he mentions casually, and I look at the land in the general direction he indicates. “There is a natural depression in the landscape, but some archaeologists happened to be up there when it was raining and noticed that several drainage routes into that depression had been enhanced and there berms built to help catch the water.”

For hours as we hike the land together, I noticed that the archaeologist and his wife move through the land the same way we do: head down.

“I am just an old trash picker,” the archaeologist’s wife says with a grin on her face.

“Aren’t we all?” I reply casually, recalling the hours I have spent in old mining sites combing through camps and tailings piles, to which she says, “No, no we aren’t.”

I nod in agreement, knowing she is right. Not everyone is captivated by the remnants of people who came before. Or maybe they just can’t see them.

We come across a more recent human sign of an old campfire on the canyon’s rock rim, full of ashes and partially burnt aluminum cans. One is a Guinness as you could still see the harp. The archaeologist’s wife, who reads the landscape in the same way as her husband, places the can back exactly where she found it. I have noticed them doing this all day long, taking great care to replace potsherds or stone tools we have found, but I am surprised to see the burnt can treated the same way. My husband notices it too and asks the archaeologist.

“As hard as it is for me to see the trash there and walk away,” he says, “when it is in a context like this it is part of the record of our presence here, which is what archaeology is.”

There are remnants of human life all over the public lands we wander—from indigenous artifacts to leather shoe soles from Victorian era miners to plastic food wrappers from the modern day camping crowd. I had created a trash hierarchy in my mind, though, in which modern trash is unacceptable but historic trash is great fun. I am in the leave-no-trace club of outdoors people and feel anger when I find trash on public lands, which I do with some regularity. To look at the ruins of a great mill with nostalgia but a great mansion with hostility is a hypocrisy to unpack.

We walk along the canyon rim and I look out on what seems to be an ocean of juniper and sage, a restful blanket of greens and browns spread out before me and I try to see it differently. With effort inspired by the archaeologist, I fight to look for rocks on top of the loess that would indicate a prehistoric site that could rise through my imagination and emerge as people who looked like me but different. They are sitting around a fire, heating rocks to cook wild game. Then what? Through this collection of rocks and colored soil can we know anything else about them?

This is more fragile territory with our archaeologist friend as our barrage of questions come back to us in facts, not narrative because that is what trashpickers get— the hard objects of a story. He tells us they saved water everywhere they could. He tells us they farmed. He tells us they migrated through this place in several different eras. He tells us their homes had a basic layout that helps archaeologists see how they organized their lives. All of that is interesting, and it changes the physical world for me in the way of a black-and-white picture turned to color. But it doesn’t give me what I want. I want to know their stories. Did they love? Did they all believe the same thing? Were there outcasts? Did they believe in evil? In God? Today we look out on largely the same external landscape, but internally is there anything that is the same? When did they start to think about things they could not see?

As the sun sinks, practical matters emerge. We are getting tired and hungry. It is getting late in the day. We have been gone for hours but have not traveled more than a mile from our vehicles. We return to camp for a snack and a sit. The archaeologist and his wife patiently keep answering our questions until it is time to go. Resting in chairs with cold drinks he shares an anecdote about dogs and how there are alot of dog bones in the puebloan cultural record. Some of them, he says, are formally buried. Some, possibly hunting companions, are found formally buried with people, and some dog bones are found in the midden (trash) pile indicating they might have been eaten. In how the dead were treated–then as now–our grief is a manifestation of our love: love of each other, love of fellow beings, and love of place.

After they go, I take a short walk from camp in the amber glow of sunset. I spook a tiny lizard and I am lucky enough to see a white granite gila open, its sweetness scenting the air.