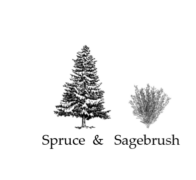

Sometimes a promised storm delivers, coming hard and fast, almost in full sheets of snow. A foot or so arrived over the past two days in just this way, and everything is white. I thought this recent storm was powdery, but my husband, who does most of the shoveling, said no, it was wet and heavy. The Inuit have more than 50 words for snow, so there is much in between wet and dry. Maybe they even have a word for the snow that husband and wife cannot agree on. In the winter I think a lot about snow, but I don’t research it to know why it changes so much from dense and saturated to light as a feather. Today as I look out on the thin aspen branch assaulted by the recent storm, I see a stack of snow sitting inches high, and I think, how is that possible?

I am tempted to grab my phone and look up an explanation for the snow sitting high and proud on the pencil-thin branch. I reason that knowing such things doesn’t take away from the beauty I see before me. As much as I can easily ignore social media, the on-demand answers the internet offers to my every curiosity is my weakness. When a question arises, I rarely stop myself from quenching my thirst from the ever-bubbling well of online responses. Query resolved, I sit back with a satisfied knowing, calmed by the illusion that everything in the world can be explained and therefore ordered, even predicted.

But sometimes, like when I notice snow reaching to the sky from whence it came on the thinnest of branches, I want to stay in the wonder. In those moments, I become aware of how profane the world has become, its resonant mysteries covered with a confetti of information like a plague of facts. We eagerly dismantle this magical whole into its infinite parts that are then studied, described and sometimes even reconfigured to predict the future. In any case, we are left with pieces of a world that, once reassembled, no longer glow.

During the short cold days of January in the mountains, I don’t fight the weather or flee to warmer places with longer days. Instead, I find myself leaning into the stillness and contemplation that seem suited to the season. I subscribe to Navajo Traditional Teachings where Diné elder Wally Brown is featured in free videos telling stories that have been passed down through generations. Recently he shared one about the Navajo descriptions of the moon in which he mentioned the “disappearing thirteenth moon.” This he described as the quiet moon in deep winter when there are no ceremonies, no loud songs. During this time families gathered together to spend time indoors sharing stories or silence, likely conserving energy in this hungriest time of the year. He went on to describe the remaining 12 lunar cycles and their corresponding months by what is happening in nature, such as the “cooking snow moon,” and “the moon of the thin wind.”

I find myself caught on that disappearing thirteenth moon, the one that is absent from the modern calendar, which he puts in January-February. It feels so resonant for me. Just as we have winnowed 13 lunar cycles into 12 months, we have dispensed with deep winter’s natural tranquility that allows us to rest in a state of wonder.

Without intending it, my family observes this often as we gather at the end of many days to play cards and share thoughts and stories, filling the time between the early sunset and bedtime in the small intimate space of our living room. In just this way, I imagine, humans grew their curiosities and discoveries about the world into tales they shared about how it all works. These mythologized explanations of the world, more poetic than scientific, are often dismissed now. As modern humans, we are fond of looking back and saying, “That’s because they didn’t know. Now we know.”

Yet just because we are piling up facts like snow drifts as we measure and test every discernible bit of our planet, in the end, what do we know and what is the cost of all this knowing? At my fingertips are answers to anything I can think to ask, and even suggestions for more related questions. Because of the secret algorithms in my search engine, those answers will be sifted and sorted and presented to me in an appealing array of formats. Wikipedia for that reference book feel; Reddit for the Q & A. Seeing my interest in science, a pop-up may offer me a subscription to Scientific American or National Geographic so I can get quality, vetted answers. Infinite scroll will entice me to stay there until the snow has melted off that branch and my ponder along with it. Likely by then the current of the surveillance economy will have me shopping for new skis and I will have forgotten the snow on the aspen entirely.

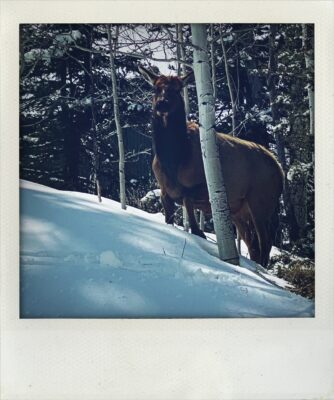

Later that day on my way home, I see an elk wading knee-deep through the snow. Where is she going? What is she going to eat today? Where are the other elk? What does she think when she sees me? I think about the encounter all the way home and let the thoughts that come fill me up until I feel myself allow for the unknown. I vow, at least during the missing thirteenth moon, to practice curiosity and resist the temptation to know because certainty is a closed state. How can I see the sacred when I have stopped looking for it? So if you know why the thin sprig holds the snow several inches high, or what the elk is doing knee-deep in the snow, please don’t tell me. I am choosing to slip into the disappearing thirteenth moon and ponder it all.