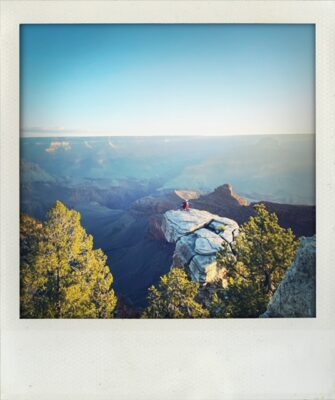

Just after winding our way up a series of hairpin turns through a red rock labyrinth in central Arizona, we emerge to a straightaway through the Ponderosa forest. Any other time of year we would be happy for that elevation, but it is April, which is a four-letter month in the mountains. Our winters are long, and by this time we are weary of cold and wind. We came south for the sun and warmth, but at this elevation this time of year, we still need pants and a light jacket. The skies are blue, though, and we are happy to be in the Grand Canyon state. We are headed to one of a few campgrounds in the area, and they are all first-come, first-served this time of year. It is already early evening. We anxiously join the line of cars at the entrance and are lucky to get one of the last open spots. When we take an evening stroll a short time later, we notice there is now a sign saying the campground is full.

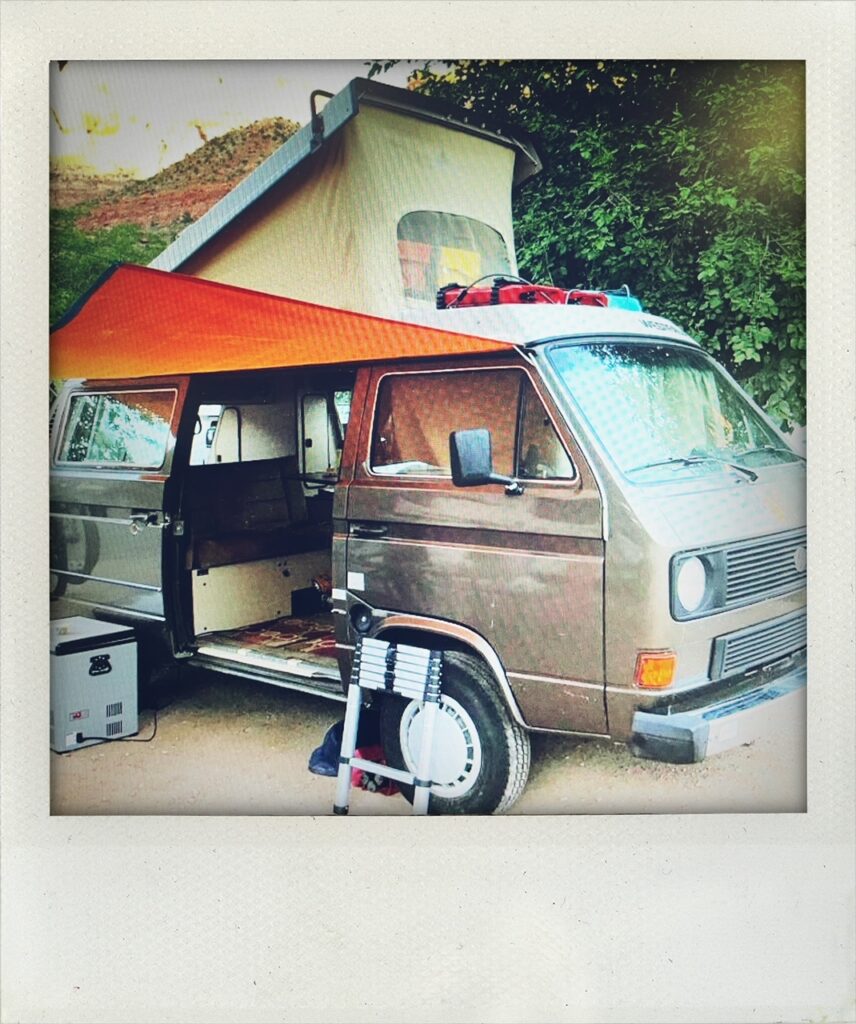

We camp a lot, but not usually in campgrounds. When we do, we like to walk around and check out the setups of other campers. On just such an outing, scrolling past the sprinter vans, classic tow-behinds, pop-ups and massive truck campers, we see a refurbished mid-1980s Volkswagen Vanagon that is pretty amazing.

“Mom, I think it would be really cool to live in a van,” says my daughter just after passing the VW. “You know, travel around, see the country.”

I take a deep inhale–during which I imagine her as a ratty haired urchin, skin lacquered with the dirty patina of homelessness, eyes glazed with drug addiction– and then exhale those fears. I try to make myself flexible, like a child, so I can climb into her wide open mind and slip on her free-spirit world perspective, full of possibilities and adventure.

It helps when I remember that she comes by this wanderlust honestly from both parents. Though it’s hard to see amidst our current burdens of property and possessions, once her dad and I both had the light footprints of vagabonds. I bought my first backpack in my early 20s to spend a month traveling Europe in the ultra-cheap hostel-Eurail style, a week of that spent alone in countries where I didn’t speak the language. Her father and his backpack hitchhiked around the country for a year before landing on Colorado’s rugged Western Slope.

His stories are legends in our family–the backpacker hitting the road with a few hundred bucks, walking miles, taking questionable rides, sleeping in missions when he had to, but more often in his tent, eating whatever (generally not much). He attended Rainbow Gatherings with the truly fringe tribe and played chess in a crack house. Dude has been around.

By comparison my story is pretty tame because, as a woman alone, hitchhiking—even traveling—has so many more risks. My backpack around Europe almost didn’t happen when my traveling partner backed out a week before I was supposed to leave. In the days before cell phones or the Internet, I felt panicked and angry that, simply because I was female, it was just too risky. I ended up connecting with another woman who needed a traveling partner who became a friend, so it had a happy ending.

Whether you go on your own or with a friend, it still takes courage and confidence to leave what you know with very little in search of something undefined. It is this willingness that led my husband and I to become travelers. I see in my daughter this openness, this nascent yearning for discovery, for finding her path, her place. She loves Colorado and living in the mountains, but the ski-town culture? Not so much. She is ultimately, like all people, looking for the right soil for her roots.

The thought of roots recalls a card I received when this daughter was born. It bore a now-common maxim for parents: “There are two gifts we should give our children: one is roots and the other is wings.” It sounds lovely, but when I try to picture it in my mind, it doesn’t work. Your roots are the very things that prevent your wings from working, and vice versa. Plants stay put, animals move around. Clearly, we are animals. So why is that quote so popular? What do we actually want to give our kids with that roots-wings thing?

My daughter is starting to spread her wings, and I see her roots start to pull at the ground, our ground, the ground we have spent our lives building. Parents know their child needs to leave, but it’s hard to watch, like seeing the external fuel tank of the space shuttle combust when it hits the atmosphere, going on faith that the rest of the shuttle–now well out of sight–is intact and on course.

She wants to be rid of our limitations, our stupid jokes, our furniture. She will soon be out of sight, possibly to reappear in a van camped on a beach in Oregon where it is overcast and rainy, finally free from all of those years of too much sun. Maybe she will talk philosophy in a coffee shop and meet others who wonder what it is all about, broad-minded types who read The Communist Manifesto because they are curious. Or maybe she will park her van near another wanderer who draws endless faces in his sketchbook as he tries to understand the people who puzzle him. Like her own private space suit, her van could take her on a search for her tribe and the answers to the questions that keep many young people awake at night: What is it like out there? Where do I fit? What if I don’t fit? What if my van is the only place I feel safe, feel like I can be myself? What if there aren’t any other people like me?

Those questions don’t worry me. I feel sure that she will find her people and her place. What keeps me awake at night are the hunters who would like nothing better than to stumble on a beautiful young girl living alone in a van, and I tell her about that.

“Knowing that is out there doesn’t need to stop you from going, but you should go with open eyes so you are prepared.” I say. “You wouldn’t hike without water, a snack and a rain jacket, would you? Same thing.”

Well, she would and has set off on many a hike without any of those things. I don’t think preparedness will be her biggest problem, either, but I don’t want to tell what worries me most: the times she will have to battle herself, to rely on her own resources to solve problems, to overcome her self-doubt, to constantly adjust her compass. Maybe I don’t tell her because this is the truly hard part. The painful part. The growth part.

Both of my kids know that our parenting plan includes them leaving when they are grown, kind of like that final concert after years of music lessons. They can come back, but they have to leave so that if they come back, it is by choice and not because they are afraid to try something else.

I recently was talking with a writer friend who said sharing your creative work is an essential part—it completes the expression. It is the same with children, who are, for many of us, our most treasured creative act. They have to be shared with the world. That is how they find their connections, their people, their place—the right mix of ingredients each of them needs to put down roots and grow. It might be next door, it might be the Pacific Northwest. Without seeking, though, she will never find.

Some kids are naturally drawn to paths that are clear and well-trodden, but some don’t, and for them the quest changes. There is no map, no quiz, no ritual to divine your life route when you leave the trail. There is only the courage to add action to the hope that you can find your people, purpose and place. One choice will lead to another until eventually you can start to uncurl your roots and plant them into the soil.

I worry, of course, about the flight, especially about the time in between the take off– when you pull your roots from your home soil–and the landing. But I also know that this can be the most exciting time of a person’s life. Like any adventure, it involves facing fears and maybe even some danger, but if you don’t take those steps, you risk becoming a watcher, a what-iffer, wondering what is out there like a macaw in a cage.

As we keep walking, I look around at all the campers, the voyagers. Some are light-footed, traveling with just their car and a tent, while others are laden with the weight of huge rigs. It makes me nostalgic for that time of uncertainty, of becoming. A time when so little had been decided and so much was possible. It is a stressful time, too, because there isn’t much security in rootlessness. It took me a long time to find my place, people and purpose, and now my roots are deep. I am bound, for better or worse, for richer or poorer, to this place where mountains and deserts live side by side.

I ponder the roots-wings phrase again, and I create an image with my own child. I see her flying with her root-feet, unplanted and dangling free, tingling in the open air with the feeling of home, of her first connections, of the places that will be part of her past that she takes into her future. It is, after all, what we do with seedlings all the time. In the human version of casting them to the wind, we send them off in a Volkswagen Vanagon, traveling around until they find the right spot to dig in and grow.

This is one of my favorites. Thank you

Thank you! Here’s to adventuring women like you!