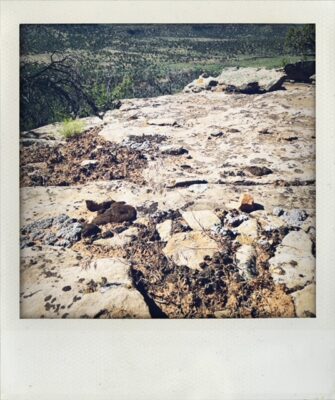

Lazing on the warm Dakota Sandstone, we gulped in the spring desert sun like thirsty hikers as we gazed at an expanse of only rocks and plants. I was blissfully empty minded when suddenly my daughter confessed to me that she used to have pretty severe anxiety about the impending zombie apocalypse.

It got quiet for a moment because, well, how do you respond to that?

“Umm, you know that zombies aren’t real, right?”

“Well, yeah, sure,” she said. “But ya know, what if? Like what would you do if it was the zombie apocalypse? I think I would get a katana sword, guns and ammo and go Kill Bill. Kind of like Zombieland. Let my warrior out.”

In response I reached deep inside, hoping to stir up my inner warrior, but there just wasn’t much there. The zombies, after all, would take care of the human population, which is the source of nearly all of my latent anger. Then I had an idea.

“Oh, I know!” I said with relief. “I would go to all the National Parks because finally nobody would be there. I would start with Yellowstone and then follow the seasons and work my way across the country. The zombies would be in the cities where the people are, so I should be all set.”

What emerged in this apocalyptic musing is that I don’t have a killer nature–I am the type who relocates bugs (except mosquitos, flies and black widows and ants in my house, but only because I can’t figure out how). I’m certain I could do it if I had to, but it would be against my ethics.

In his famous book Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold distills ethics in a beautiful passage: “An ethic, ecologically, is a limitation on freedom of action in the struggle for existence. An ethic, philosophically, is a differentiation of social from anti-social conduct.”

Whether we are aware or not, ethics drive the internal algorithm that influences the thousands of behavior choices we all make every day. When you act in accordance with your ethics, you are a person of integrity, which makes you integrated, whole. When your actions contradict your ethics, you act like a hypocrite, which comes from a Greek word meaning “to pretend or act a part.” I display both, as everyone does, but in my experience, integrity feels good and hypocrisy doesn’t.

For most of Western culture’s existence, the social ethics that Leopold refers to have applied to people and, by extension, pets. People who mistreat animals, while not always criminal, are rarely held up as ethical models. With the dawn of the 20th century, the American wilderness that seemed endless was being visibly erased by modern culture. More and more voices began to speak out and urge the ethical treatment of natural environments. Leopold’s 1949 essay “Land Ethic” codified this in a way that has become a primer for conservation-minded people. Its evolution reached popular culture in 1970 when America established Earth Day.

Like countless others, I had my own land ethic well before I ever read Aldo Leopold. And now, in the spring of 2025, with Earth Day recognition as common as recycling bins and stainless steel water bottles, it is clear that most Americans have at least heard about the environmental impact of our highly consumptive modern society. Earth Day urges us to develop and implement our own land ethic.

When he looks back for the why, Leopold sees the Judeo-Christian worldview in the driver’s seat: In the essay he writes, “Conservation is getting nowhere because it is incompatible with our Abrahamic concept of land. We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us; when we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

The 2022 Earth Day Google’s Doodle showed before-and-after pictures of glaciers and rain forests and coral reefs to illustrate what has been happening to our planet, and it really didn’t represent a lot of love or respect. It might have been too much–it sure stuck with me–because the 2023 Earth Day Google Doodle was a cartoon of forest critters hanging laundry out to dry, planting gardens, putting in solar panels and riding bikes. In 2024 as well as today, Google displayed beautiful aerial views of our planet forming the letters and I felt better, like the cartoon critters had fixed everything with their eco-friendly activities.

I don’t have solar panels, and I drive a 4-wheel drive SUV with gas mileage nobody would envy, but in some ways I follow the forest critters lead. I have a land ethic that helps me choose to participate in community supported agriculture and buy food from local organic farmers. It encourages me to commute to work often on my own two feet. It makes me think about every purchase I make and routes me to thrift stores more often than department stores. And I do these things not because of anything Abraham said or did.

I also know that, typical or not, I am an American. Anyone who is curious and has access to a search engine can probably tell you that, as a country, we could do better at sustainability, even among industrialized nations. Of 180 countries rated on the Environmental Performance Index in 2022, the U.S. ranks 43, below most developed countries, yet we are the second largest producer of greenhouse gasses (ouch). As I look at myself, I see that I grow exactly none of the food I eat, nor do I make any of the clothes I wear. I have more stuff than I need. By most indications, I am not strikingly different from most of my fellow 300 million Americans right now, so I don’t want to tell the other 8 billion people on the planet what to do because I really don’t know what to do to fix the problems in the 2022 Earth Day Google Doodle.

I like to think that having a connection with wilderness is what turns on the light of ecological awareness, and I think it did for me. Since moving to the Rockies I have evolved a land ethic that I can live with and by. For others, this epic landscape seems to light up their need to own precious and beautiful things, like a large diamond or a painting by an old master or a 25,000-square foot home in mountain wilderness. I live in a place of immense natural beauty side-by-side with some of the most extreme resource abuse I have ever seen: enormous homes that guzzle energy while standing vacant much of their existence, like a buffet prepared anew every night but only eaten a handful of times a year.

This is not unusual in Colorado’s Western Slope, where a map of counties in our state that have high house vacancy rates are the ones that run along the north-south route of the Rocky Mountains. Statewide home vacancy rate is 9%, but these 10 counties have rates above 40%: Gunnison, Park, Jackson, San Miguel, Custer, San Juan, Grand, Summit, Mineral and Hinsdale, with the highest being Hinsdale County at 71.8%. That means in almost all of the most wilderness-dense parts of a wilderness-rich state, nearly half of the homes that wilderness was destroyed to build don’t have full time residents, and 89.5% of those vacancies are for seasonal or occasional use.

And these homes are typically not small. They are luxury homes, and as such, most qualify as mansions clocking in at more than 5,000 square feet. Common amenities are heated driveways, air purification systems, and automated everything–lighting, sound systems, security, heating, air conditioning. Even though these homes may be occupied only a few weeks a year, they are maintained, heated and cleaned as if the homeowners were about to arrive. Without a doubt, these people have a different relationship with the Earth than I do.

In his provocative book, “Billionaire Wilderness: The Ultra-Wealthy and the Remaking of the American West,” Justin Farrell, a Yale professor and a native of Wyoming, pals around with this group in an effort to understand this contradictory ethic. He learns that for these people, the mountain west is, essentially, a living theme park where they can go to have a certain experience that prioritizes escape for rest and relaxation, which they have earned through their hard work. It also includes, sometimes, dressing like a western mountain town local. Whether that means wearing Wranglers and cowboy boots or zip-offs and Seattle sombreros, they like to put on a costume that shows them starring in their own particular Western mythology which supports, by extension, their self-image that by looking the part they actually are a part of local culture. They feel like nature is a great equalizer, and they think that they are friends with the people they employ. They also believe it is their money that keeps these mountain towns afloat, and the locals should be much more appreciative of that reality (this is a sentiment shared by many tourists, also, as mountain towns make for very expensive vacations). They bought their tickets to the park and expect to get what they paid for.

An even more articulated view of this sentiment came out during the pandemic when Gunnison County–hit very hard very early by COVID–asked second home owners to return to their primary residences to alleviate the strain of the non-resident population on medical and emergency care. In a High Country News article, “When COVID hit, a Colorado county kicked out second-home owners. They hit back,” by Nick Bowlin, he cites this frequently expressed resentment from a second-home owner Facebook group GV2H & Friends Forum: “Our money supports all of the people in the valley,” wrote one man. “Where is the appreciation and gratitude for the decades of generosity?” wrote another. These non-residents also expressed how the pandemic precautions impacted their experience. Bowlin relates, “People were irate when the county declared a mask mandate on June 8. ‘We come to decompress, to relax, to regenerate!’ one person wrote. “That’s a pressure we don’t need! Or don’t WANT, which isn’t a crime either!”

Needing and wanting a community of people to be extras on the set of your personal Western drama does not make them so. The residents and workers who keep such towns going have lives, families, mess, tragedies, celebrations–and these all play out amidst the exceptional natural beauty they call home. They can’t set aside everyday reality to provide the “mountain town” experience their realtors sold them.

I am angry now, the same kind of anger I feel when I hear someone make a racist joke or oppose basic human rights or when I see the fragile alpine tundra suffer beneath the harm and indignity of trash and toilet paper. It is the anger of witnessing the privileged bulldozing over whatever is in their way as they soldier forward in a tank built by money, oblivious to the destruction they leave in their wake. It is an anger of righteousness, the same righteousness that fuels the racist, the homophobe, and the ignorant pooper.

At that moment, when my anger is hottest, when it makes me wanna holler, I see it. I see how I can be just like them, like us all in our worst moments, and it stops me cold. There is no right. There is just my ethic, which happens to conflict with their ethic. Ultimately, the Earth, as the host organism we all live on, will have the final say. And walking to work instead of taking my car is unlikely to change that.

So I don’t tell people what to do. I don’t share my feelings about their purchase of endless plastic water bottles or their constant consumerism. Even more, I remember my countless single-use plastics (like the plastic wrapper I took off my cauliflower last night) and the two new pairs of shorts I just bought (they are super cute). Because though I do believe people can change their beliefs and behaviors, and that may help the Earth and its ecosystems–consider bald eagles, California condors, and Humpback whales–I honestly don’t know what makes some people stop drinking water from little plastic bottles and others not. Shaming them? Educating them? Inspiring them? Or maybe I can just live among them peacefully and realize that I can control only what I do.

I suppose that I see the Earth the way some religious people see the afterlife: that there will be a judgment day, a time of reckoning when I will have to answer to the Earth for my choices and behaviors. In that moment, I want to feel like my actions that aligned with my ethics are greater than the ones that didn’t. That allure of integrity is the angel on my shoulder that makes me consider my choices throughout the day, every day. Often it is annoying and burdensome, like when I am carrying an armload of crap to the car because I forgot to bring my bags. Or when I repair things I own and don’t really care for to avoid buying something new that I might like a whole lot better. Or when I walk my tired butt down to the bus instead of getting in the car. In the end, I feel better when my actions match up with my ethics. Every time. And there is nothing Earth-transforming about any of them. They are small choices in the face of the aggregate human impact in the 21st Century. I don’t think I am saving anything, but that’s not what I am trying to do. Instead I am trying to integrate my beliefs and my actions, falling short often, but hitting the mark sometimes, too, and when I do, it feels good.

Amen!!!!!

Thanks Judy!!